Inside Track: Bob Stuart, MQA

David Price talks to Bob Stuart about his illustrious career, shaping audio’s future…

For the first time ever in its twenty-year history, an audio engineer has won the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Prince Philip Medal. Of all the possible recipients in the hi-fi industry, it surely had to be Bob Stuart. He got the gong for, “his exceptional contribution to audio engineering, which has changed the way we listen to music and experience films”, no less. Previous recipients include the inventor of the turbojet engine, Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle; geothermal power innovator, Lucien Bronicki and the electrical engineer who revolutionised fibre optics, Dr Charles Kao. Could it be that the engineering community is suddenly taking sound seriously?

“One never truly knows which aspects prompted this award,” Bob tells me, “but it’s given once every two years to an engineer who they feel has made a contribution to engineering, education and knowledge, I guess. It’s interesting, the people who’ve won it in the past have done quite different things. I think the two things that are unusual in my career are the work we did around standards – Meridian Lossless Packing (MLP) in DVD-Audio and Blu-ray, and more recently Master Quality Authenticated (MQA).”

This award is yet another illustrious moment in a career that spans nearly fifty years. “I always wanted to design audio products,” he tells me. “All the way back to when I remember making my first crystal set – and before I went to university, I designed a tape recorder so I could have music.” In other words, Bob was, is and always has been an enthusiast, through and through. That has led him along a unique career path that saw him co-found one of the UK’s most respected hi-fi companies (Meridian) in the nineteen seventies, and champion the cause of active loudspeakers and digital audio in the eighties. In the following two decades, he helped to standardise high-resolution digital audio with the DVD-Forum, and latterly Blu-ray. Then in 2014, he launched MQA – a digital audio format that’s gaining serious traction in the recording and hi-fi worlds.

All the more surprising then, that Bob isn’t some self-proclaimed guru figure with a messiah complex – indeed he’s quite the reverse. If you’ve ever met him, you’ll know he comes across as a quintessential English gentleman; he’s quiet, reserved, polite and consensual in his approach, but with a precise and matter-of-fact manner. Listen carefully to what he says, and you feel you’re tapping into the knowledge of someone with an immense experience of the audio industry.

GENESIS

_david_j_price__large_full.jpg)

Allen Boothroyd and Bob Stuart - by David Price

"My first job in hi-fi was in 1972 with Lecson”, he tells me. “That’s where I met the industrial designer Allen Boothroyd, and we got an award from the Duke of Edinburgh for the AC1/AP1 preamplifier and power amplifier. I did the inside, and Allen did the outside, and we got on so well we started a product design consultancy. But I got a bit frustrated because we tended to be called into companies much too late. That was great for Allen because people would say, “we’ve got this product, can you put a nice box around it?”, but it was much harder for me when they asked, “can you make it sound better” at the last minute!”

Lecson AC1/AP1

He continues: “So around 1976, I said to Allen in a somewhat tongue-in-cheek way, “Rather than consult for all these flaky companies, let’s start a flaky company of our own!”, and Meridian followed. We had a good working relationship which lasted for forty years – and our design approach was cooperative synthesis.”

“Allen was a terrific guy, very easy going – he put up with me for forty years! He was very collegiate. When he picked up his pencil, the magic happened. We worked very well together. I would never quibble with his designs because he had such a great talent. The M1 was the first example of our synthesis approach – we learned how to trade aspects of the design, so we’d end up with something sculptural but also completely functional for audio. Back then the idea of having industrial design in consumer products was pretty new. I think probably Braun and B&O were notable exceptions, but pretty much everyone else used ‘draughtsmen’.”

“My interest was in great sound – initially in analogue and in loudspeaker design. The very first product we did was very unusual – the M1 was an active three-way. And then when digital came along, I was very interested in it because it was possible to remove some of the limitations for a loudspeaker designer. I was interested in digital for the things it did right, like pitch stability and bass.”

Meridian shipped its first Compact Disc player – the MCD – just six months after the Philips original upon which it was based, back in 1983. “It was a CD100 that we ripped apart; we made changes to the oscillator and replaced the analogue stage. Then we went on from there to design a whole series of Compact Disc and then DVD players”, Bob remembers. “Around 1987 the S/PDIF digital interface came out, and we pivoted our active loudspeaker designs to digital, and then to DSP. That was the beginning of us working on digital signal processing, figuring out how we could get the best sound to the listener.”

Meridian MCD CD player

One central driving force behind Bob’s philosophy is real-world design; he’s interested in making technology give practical solutions to daily problems. His early active loudspeakers – with their smaller footprints and taller, narrower dimensions – were totally out of kilter with nineteen seventies and eighties convention, but proved eerily prescient. “You can put together a turntable that plays a piano that makes it sound like it’s standing on the ground and not floating in space, but it’s big and expensive to do. The great thing about CD was that it brought that sound to many more people – it was easier for the average consumer to just play it. It doesn’t mean that vinyl’s wrong, but you’ve got a different hobby that includes changing the needle!”

“My philosophy going right back to our early speakers was if you want to make hi-fi easy for people to listen to, it’s better if it creates sound in a familiar way – by that I mean, we have this extraordinary ability to interpret nuance and space in sounds coming from human sources; the M2 speaker and beyond were us trying to make loudspeakers ‘talk’ in human scale.”

REVELATION

The eighties and nineties were harvest years for Meridian as the company established itself at the very top of the hi-fi tree, but Bob found himself a player in something larger still. “As soon as I heard about DVD, I thought now we can put enough information on a disc for it to sound really good, so let’s put out a proposal about how to do music better. I’d become involved with Acoustic Renaissance for Audio – an advocacy group started by Hiro Negishi of Canon and Raymond Cooke of KEF. In the early nineties I had become the chairman of ARA, and for the high-resolution disc initiative formed a technical committee in the UK and Japan that included Tony Griffiths from Decca, Hideo Yamamoto from Pioneer, David Meares from the BBC, Professor Malcolm Hawksford and Michael Gerzon.”

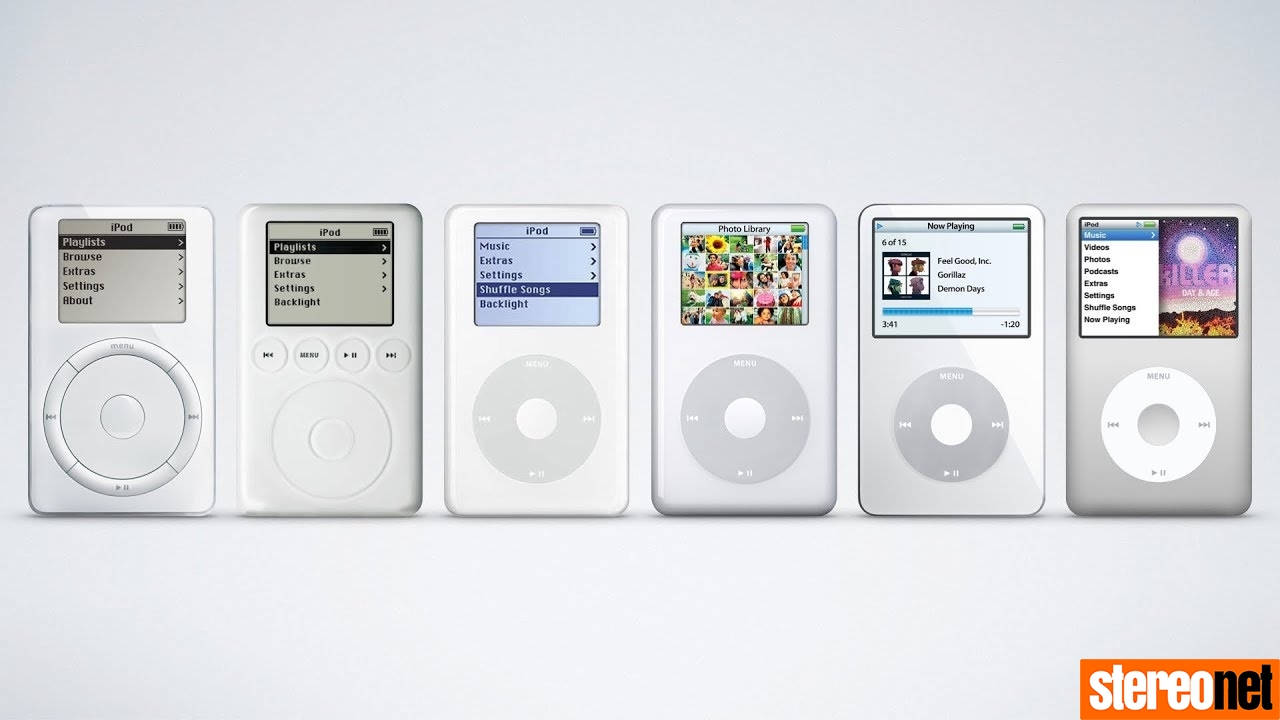

“Initially DVD was being considered only for video, so we made this proposal for using (previously unheard of) lossless compression to give multichannel high-resolution surround sound, and then six months later I got phone calls from the music industry saying “come and play this to us". It was an exciting time for digital audio. David Chesky and Pioneer started selling 96/16 music on DVD discs. In parallel in Japan, there was a movement pushing for 96/24, Pioneer was involved in that. The exciting time came when the DVD Forum and key music labels decided to do an audio disc. I was able to demonstrate the clear superiority of Meridian’s MLP and get ‘lossless’ into the format. For me, the new DVD-Audio standard was able to give enough capacity to really capture great sound. But sadly DVD-A and SACD had a format war, and the iPod won! This showed that in general, consumers always vote for convenience. That’s a lesson well learned, and it informed my later work with MQA.”

When Meridian sold MLP to Dolby in 2006, it was renamed Dolby True-HD and later appeared in Atmos – and many people subsequently forgot about it. Yet Bob remembers ‘lossless’ as controversial in its day. “It was quite a challenge for the very conservative audio industry, back in the mid to late nineties”, he explains. “I introduced lossless compression as the way to get all the quality we wanted on to optical discs – we wanted to address storage capacity. They were controversial ideas. I remember sitting in Tokyo with music labels, doing listening tests to show them that MLP didn’t sound different. When you’re trying to change an opinion – you really have to do it one at a time.”

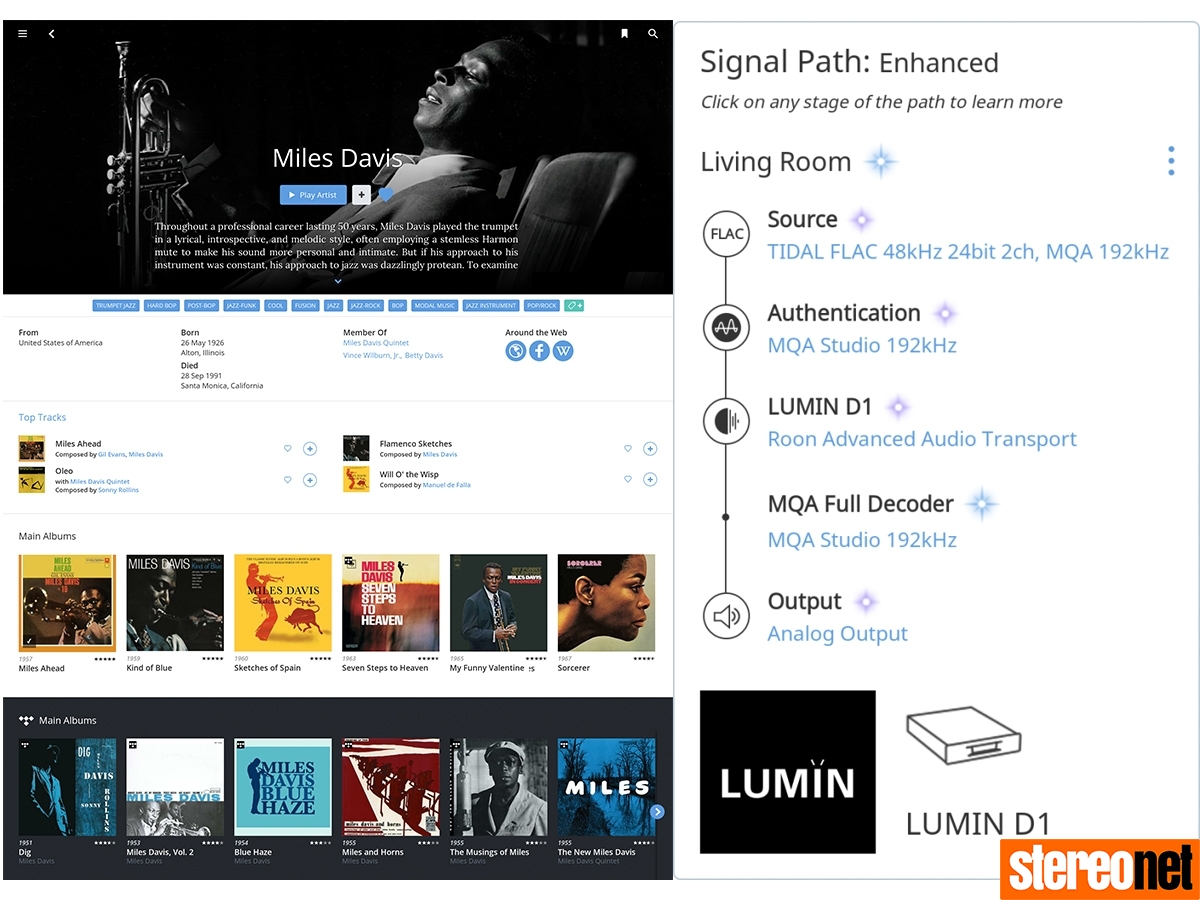

“Indeed the first three years of the MQA project was talking to mastering engineers, recording engineers, label engineers and even a few artists saying, “okay, we’ve got something we’d like you to listen to, let’s listen to your recordings on your gear, what do you think?” One conundrum was when many engineers said, “you’ve made it better, more like the studio.” It’s very hard to communicate the idea that you can make something better rather than just preserve it correctly. We knew that was true because with MQA we’ve taken away the side effects of the technology all the way through the recording/replay chain. We wanted to tackle not only the fundamentals of how should you capture a sound in digital, but how you should play it back. And also we needed to make sure how it gets to the listener, which is why the authentication part was added.”

As well as being a long-time advocate for outstanding sound for the consumer, Bob is passionate about helping to preserve entire music archives. “It’s about the journey from the studio to the listener”, he says. “What we’ve been doing with MQA is making sure that natural sounds are captured in a way that is totally satisfying, meaningful and deliberate. That’s why we’ve been active in supporting live streaming, because wherever there’s sound, MQA fits in. All the problems in the pipe are fixable. If we think about video, everybody gets upset if you try to take them back from 4K video to VHS, but people aren’t always as confident with sound. Fewer people are as sure of their hearing as they are of their vision, yet it should be the other way around because hearing is more immediate and more precise and more fundamental to our survival.”

Bob broaches the subject of psychoacoustics. “Music has a tremendous connection as the soundtrack of our lives. This complicates what we do because the worst sin is to be arrogant about ‘good enough’. What we’ve learned in the last fifteen years is that you can’t treat the human as a kind of black box – our hearing is non-linear. We don’t hear things, we listen to them. What brain science has been able to show us is that we are actively listening to something – so when a sound is happening, we’re tuning our ears, changing how they work. While listening to an orchestra, we can focus in on the flute. When there’s a conversation, we can guess what’s coming next. We reach out for it. It’s an active and edited process – this is what evolution got right. There’s no way an animal can devote all its resources to being able to take all that information in at one time. We’ve all adapted to what was needed.”

QUALITY ASSURED

“We’ve had a different problem introducing MQA than we did with hi-res audio on DVD, says Bob. “The DVD Forum and Blu-ray Forum were multinational groups centred in Japan, where there is a tendency to respect collaboration. You know the Japanese saying that, “when we all cross the road together, no one gets hurt”? In the Blu-ray Forums, we had other kinds of companies – like Disney, Microsoft, Apple and Intel – than the DVD Forum, where there were entries from Matsushita, DTS and Samsung. We were this little company from the UK, whose MLP system worked so much better than the others that they really had no choice but to adopt it. That process was interesting and involved having the music industry very much on-side. Back in the day, you had to have standards, you couldn’t produce anything in the CE world without one. Nowadays though, MQA doesn’t really have a competitor and isn’t part of any international standard.”

“That’s one reason I first launched MQA in Japan”, Bob explains. “There’s a strong culture of respect and deep interest in high resolution, plus it’s a place you can test ideas because it’s very much a pond on its own. We announced MQA there in August 2014, and in the UK and USA in December.

Peter Craven has been a long-term friend and collaborator – we knew when we did the research into MQA, there would be controversy somewhere. In fact, when I realised we were about to turn over some ‘sacred cows’, we did ask each other “Do we have the energy for this?” But obviously, simultaneously improving quality and convenience was irresistible! We know there would be controversy – we didn’t know if it was going to be on the professional audio side, on the AES side, on the audiophile side or on the academic side – it turns out in the end that there was only a little bit of controversy from those who really didn’t understand the question! Most people understood what we were doing, and those who really understand MQA are impressed.”

Generations of iPod Classic

For Bob, the iPod was a dark moment. “Sure, it helped to discourage piracy, but it was the beginning of a very long decline in audio quality; two generations have grown up not really having access to high quality recorded music. CD wasn’t perfect, but it was a lot better than compressed audio. Fast forward to now, and people think that recorded music is what comes out of a DAB radio in the kitchen; they don’t know that recorded music can be so satisfying!”

He continues: “Recording and then mastering engineers do all this good work, then when they get to the end of the line, they send out an MP3! When downloads started to become a thing, there was a lack of discipline in distribution – so files could be upsampled, or downsampled – and nobody knew what they were getting. It caused a lot of grief to top-line mastering engineers. MQA directly addresses this consistency and traceability issue, as well as carrying the music in a much better format. MQA was surprising to many people, so it generated controversy, but curiously only inside the audiophile world. People would write negative stuff about MQA because it gets more clicks than anything else. When all is said and done, MQA is based on solid science and is approved by the guys who make, master or curate the original recording.”

Bob is sanguine about his ongoing task to get MQA accepted by the world. “Maybe there are one or two companies who don’t want to do MQA, and that’s fine – but there are very many high-performing companies who understand, not just that it’s important for their business, but that it actually works very well! The ones that do include some of the best – dCS, Berkeley, EMM Labs, MSB, Meridian, Esoteric, Luxman and scores of others – and of course they can play back PCM and DSD in their chosen way – we only specify and calibrate MQA. We’ve now launched with Xiami Music in China and continue our collaboration with TIDAL, and have an ever-increasing list of companies with rapid growth in the USA, Japan, Korea and China.”

“We’re trying to deliver great sound to everybody,” he explains, “but in the modern digital era it’s absolutely chaotic; for example, if you go to a record label, you could find fifty different versions of the same song, all in different formats. In the old days, you had an LP master, a cassette one and then later a CD one – now you’ve got Windows Media Audio, streaming, WAV, AAC versions, whatever. The decline in sound quality is marked – it seems like more people listen on Alexa speakers than anything else. These are some of the things we’ve wrestled with because we wanted to fix the distribution – from the studio to the end-user.”

I put it to Bob that MQA is basically ‘good housekeeping’ for music, yet still many audiophiles aren’t aware of the need for it. “No David, they’re not all aware because they don’t know what’s going on inside the box”, he tells me. “We’ve seen instances when the signal comes into the box and undergoes four different sample rate conversions before it gets out. To use a photographic analogy, we’re saying it’s about having the right lens with which to take the picture, rather than just thinking about the file used to convey the photograph or worse, later adding colour to make up for avoidable blurring.”

“In the old days,” he continues, “when vinyl was cut, the exact process was that at some point someone in the mastering studio said “that’s it”, and that would be captured. That was then taken to a different room and then cut. Some copy masters were made, but that was it. When you bought the disc, it was a ‘print’. No-one could change it in distribution.

The key thing is with MQA is that we can take you back to the original master. With early digital, the technology was very basic; there were inherent problems in A-D converters and in processing. When workstations came in, mastering guys could use compression and equalisation to make them all loud. In some cases we prefer to go back to the originals, bypassing this.” He notes that some analogue master tapes from the nineteen fifties, pre-Dolby, are absolutely superb sounding. “It’s a wider bandwidth than CD, and is human-friendly…”

For modern recordings – fast forward to companies like 2L who are using MQA all the way through the recording process – we have the chance to get an extraordinary level of transparency.” MQA is now used in the whole of Warner Music new and back catalogue, and Universal’s too – plus Sony is coming, and a lot of the independent labels including from China and Japan. Bob continues: “We’ve got companies now making products who in the beginning said “no way” to MQA – but have now come round. We never had the professional engineering community against us, and that’s got us to where we are now.”

BANG A GONG

"One of the things I’m particularly pleased about with my award is that, just maybe, it has the chance to raise audio engineering to a higher level”, Bob says. “If you look at other kinds of engineering that have been awarded, it’s not audio – so this is unusual. The audio industry has tended to be made up of hundreds of small enterprises, there have been very few companies that could stand up and say, “let’s make a standard”. That was done when for vinyl LP and CD, but apart from that it has been rare. Although standards can be constraining, not having a clear message leads to customer confusion. The audio engineering community hasn’t been able to come together to create the weight that lets it argue with the video side, but maybe now times are changing?”

David Price

David started his career in 1993 writing for Hi-Fi World and went on to edit the magazine for nearly a decade. He was then made Editor of Hi-Fi Choice and continued to freelance for it and Hi-Fi News until becoming StereoNET’s Editor-in-Chief.

Posted in: Hi-Fi | Technology | Music | Industry

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION

Want to share your opinion or get advice from other enthusiasts? Then head into the Message

Forums where thousands of other enthusiasts are communicating on a daily basis.

CLICK HERE FOR FREE MEMBERSHIP

Trending

applause awards

Each time StereoNET reviews a product, it is considered for an Applause Award. Winning one marks it out as a design of great quality and distinction – a special product in its class, on the grounds of either performance, value for money, or usually both.

Applause Awards are personally issued by StereoNET’s global Editor-in-Chief, David Price – who has over three decades of experience reviewing hi-fi products at the highest level – after consulting with our senior editorial team. They are not automatically given with all reviews, nor can manufacturers purchase them.

The StereoNET editorial team includes some of the world’s most experienced and respected hi-fi journalists with a vast wealth of knowledge. Some have edited popular English language hi-fi magazines, and others have been senior contributors to famous audio journals stretching back to the late 1970s. And we also employ professional IT and home theatre specialists who work at the cutting edge of today’s technology.

We believe that no other online hi-fi and home cinema resource offers such expert knowledge, so when StereoNET gives an Applause Award, it is a trustworthy hallmark of quality. Receiving such an award is the prerequisite to becoming eligible for our annual Product of the Year awards, awarded only to the finest designs in their respective categories. Buyers of hi-fi, home cinema, and headphones can be sure that a StereoNET Applause Award winner is worthy of your most serious attention.